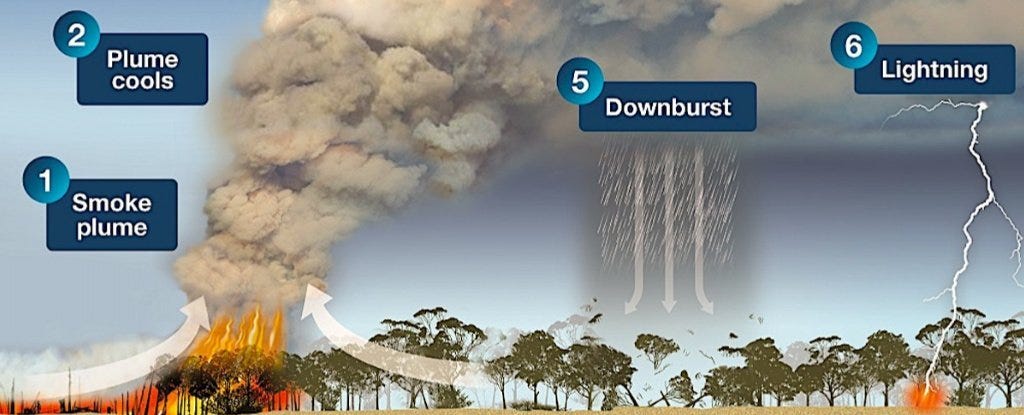

The smoke from the Australian bushfires have, on occasions, soared over 17 kilometres up into the stratosphere, creating their own weather systems, including thunderstorms and lightning strikes that start new fires. NASA predicts the smoke will travel all the way around the globe and back to Australia. Many have claimed that arsonists are to blame but only one percent of the land burnt can officially be attributed to arsonists.

For decades, scientists have warned us about the consequences of inaction on climate change. Their predictions seemed, for many, to be a problem far off in the future. In 2019, Australia stumbled unprepared into that future. Whilst the bushfires themselves have been described as unprecedented in scale, intensity and duration, it’s important to put them into the context of all the other events experienced on this continent in 2019.

An extreme heat wave in January 2019 resulted in Adelaide recording its hottest day of 46.6 degrees, while Port Augusta, 300km further north hit a record temperature of 49.5 degrees Celsius. In December and January an estimated one million fish died in the Darling River in three mass kill events as politicians blamed the drought for the lack of water in the river.

The extended drought is, of course, the backdrop to the bushfires, heatwaves and mass fish deaths. According to BOM, the 3 years from January 2017 to December 2019 have been the driest on record for the Murray-Darling Basin and the state of New South Wales (NSW), as shown on this map.

After a long drought, Townsville in North Queensland experienced an unusual, extended period of heavy rainfall resulting in flooding in February 2019. According to the Bureau of Meteorology (BOM) “the accumulated totals from consecutive days of heavy rainfall were the city’s highest … since records began in 1888”. Two people and an estimated 500,000 cattle perished, while 3,300 homes were damaged. At the same time Tasmania was experiencing unprecedented bushfires.

Such extreme weather events are precisely what climate scientists predicted as the climate warmed. Average temperatures across the globe have so far warmed just one degree Celsius above the average pre-Industrial levels. It sounds so insignificant. Just one degree, yet on a fragile and dry continent like Australia this small change is already wreaking havoc. Have we hit the first tipping point? Can we hope that next summer will be back to the relaxing summer’s of our past or should we now expect more — and more intense — weather events in the future?

While there were some wild stormy days in winter, the overall winter rainfall was low and so the bush was very dry, providing fuel for the coming fires. In September, at the beginning of Spring, the bushfires started. Australia experiences bushfires almost every summer and a large proportion of Australia’s plant species are fire tolerant, fire resistant or fire dependent. That is, some species need bushfire periodically in order to propagate. Australia’s First Nations people managed the landscape with fire, periodically burning sections of their Country. Regular small fires at cooler times reduced the risk of large unmanageable bushfires in Summer. Yet cultural burning is a continuous process of active management by all communities across the entire continent. It was embedded in the way of life. The approach varied according to local conditions and has the aim of keeping ecosystems in balance and encouraging an abundance of life. Modern bushfire management is under-resourced and its aim is to reduce risk to human life and property.

In November, we were in East Gippsland in Victoria and heard about the bushfires in southern Queensland and NSW. I have never felt so worried and sad as when we travelled back to Sydney for Christmas. For most of the eight hour trip we drove through a smoke-filled landscape. It was dark in the middle of the day and we drove with our headlights on. The sun was a red circle in an eerie sky. Canberra, Sydney, and Melbourne have all experienced many smoke-filled days this Summer. By the time we arrived in Sydney we were regularly hearing the advice that we should stay indoors, not do strenuous activities and wear a face mask. The Air Quality Index was regularly at levels deemed hazardous to human health and on a number of occasions reached as high as twelve (12) times the hazardous level. For much of December, in the lead up to Christmas and the New Year, the usual joy was subdued as many communities were suffering.

As of 14 January 2020, 18.6 million hectares were burnt, 5,900 buildings (including about 2,683 homes) were destroyed and 33 people killed. The selfless and tireless work of thousands of mostly volunteer fire fighters has been instrumental in minimising the loss of lives and property.

An earlier estimate suggesting 480 million mammals, birds and reptiles were killed has now been revised to one billion. Some endangered species may be driven to extinction, while ancient rainforests that never burn have also burnt.

After catastrophic conditions on New Years Eve and in early January, the risk has now subsided somewhat although many fires are still burning. The northern wet season can bring occasional milder weather and more rains to the south of the continent. The north of Australia is tropical and usually experiences monsoon weather from November to April but the period of heavy rainfall is getting shorter and this year the first tropical cyclone arrived in early January.

Australia’s weather has always been quite variable and one of our problems is that when Europeans arrived on this continent, we assumed that Australia experiences the same weather variations throughout the year as in Europe — Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter. Yet not only do weather patterns vary widely between the tropical north, arid interior and temperate south but the variations between years are sometimes more significant than those within the year. First Nations people had a deep appreciation of these fluctuations and, together with their respect for the land and other species with which they lived, this informed their land management practices.

By contrast the modern relationship to land is having a substantial negative impact. This is not just about the burning of fossil fuels, creating the greenhouse blanket that warms the entire planet. In Australia, our negative impact includes the failure to manage the precious little water that falls on this continent. Mining and farming practices extract and use water without accounting for the significant natural variability — from year to year — in the availability of water, lurching as we do from droughts to floods. Although Australia naturally experiences periodic droughts, the frequency and severity of these can be dramatically influenced by our farming practices, particularly the way we collectively manage water. Yet like most current economic practices, our farming practices are extractive. We simply take whatever water we need.

The Murray-Darling Basin — the most drought affected zone as shown in the map above — has the most contested water in the country. The Murray-Darling River Basin starts in southern Queensland, passes through much of inland NSW and Victoria before reaching the Southern Ocean in South Australia (SA). This is the largest and most complex river system in Australia. Over 9,200 irrigated agricultural businesses rely on it and SA depends on it for 83 percent of its water. Low flows in the river meant that dredges were needed to keep the mouth of the river open between 2002 and 2010. The Murray-Darling Management Plan was introduced in 2012 to manage the demands of irrigators and ensure there was sufficient flow out to sea without dredging. Yet as the next drought cycle commenced we simply re-commenced the dredging of sand in January 2015 and this continues today.

The contest between extractive economic activity and the needs of the environment are nowhere more starkly obvious than in the Murray-Darling Basin. Australia is the driest inhabited continent on earth and water extraction for agriculture that damages river ecosystems can only end with both the ecosystems and the economy that depends on water collapsing.

By contrast, regenerative agriculture seeks to build soil volume and vitality, enabling it to capture and clean water thus encouraging an abundance of life. Extractive farming, usually as monocultures, eliminates all species but those that return a profit. Regenerative farming supports and encourages a rich diversity of life. Instead of just taking from the land, regenerative farming practices give back in equal measure. This is the circle of life and applies not just to farming but all aspects of our economic activity — never take more than you give.

Charles Massy’s Call of the Reed Warbler: A New Agriculture, A New Earth identifies the principles of regenerative agriculture as follows:

- Maximising the capture of solar energy in all plant species;

- Improving the water cycle, maximising water infiltration, storage and recycling in the soil;

- Creating healthy soils that contain and recycle a rich lode of diverse minerals and chemicals;

- Maximising biodiversity and health of integrated, dynamic ecosystems at all levels.

As we rebuild lives, homes, businesses and communities, regenerative practices will help create a deeper understanding of our place on this continent and our responsibility for managing it.

As we rebuild we ought to re-imagine all aspects of how we live on the land, how we generate energy, how we manage water, how we produce food and how and where we build our homes. A systems approach to rebuilding our towns and communities might think in terms of a local renewable energy micro-grid, a local water micro-grid and a local integrated bio-diverse food system. This would allow communities to collaborate as they harvest, store and distribute their basic needs — food, water and energy — locally. In turn, this would not only build local resilience and create local work opportunities but also build the natural ecosystems upon which all societies and economies depend.

Steven Liaros is a Director of town planning consultancy PolisPlan.com.au and author of ‘Rethinking the City’ — an exploration of the historical ideas that underpin the organisation of cities — showing how these ideas are being transformed by the Internet. With qualifications in civil engineering, town planning and environmental law, Steven is currently undertaking a PhD research project at the University of Sydney’s Department of Political Economy. He has visited our WELCOMMON. We have asked him to write an article about the current situation in Australia, We thank him